Use of Cookies

Our website uses cookies to facilitate and improve your online experience.

Climate change, at heart, is a spiritual problem. While we can point the finger at rising CO2 emissions, on a deeper level the cause of the climate crisis is the absence of spiritual values and collective vision by human communities. Many people I see in my work in hospitals, prisons and the community have succumbed to anxiety, depression and despair; I feel this is because of not feeling a deeply intimate sense of belonging to the human and Earth communities.1

As we move towards the United Nations Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) number 11: “Make cities and human settlements inclusive, safe, resilient, and sustainable” understanding Zen Master Dogen’s Tenzo Kyokun is vital. It contains practical actions we can all take to be in better sync with the larger rhythms of the planet, and to feel a sense of belonging. Dogen asks us, for instance to be frugal with food, treating it as if it were our own eyes.

Putting Dogen Zenji’s Instructions for the Cook into our modern context, we must first understand that cities are intimately connected to farms. In agricultural societies in the past, the connection with the land was obvious. People knew the field where their rice or chicken came from, or they knew the people who harvested that food. This is largely not the case in many cities in the world now. Since the Industrial Revolution of the 18th century, humans have become increasingly forgetful of the land on which we live, and grow our food.2 What we purchase at the grocery store may come from several hundred miles away, or even the other side of the planet, making our connection with the Earth appear invisible or irrelevant.

To complicate matters, roughly half of the world’s population today lives in cities, which are largely designed without the natural world in mind. Cities are planned to accommodate human convenience, with paved roads, buildings, housing, and occasional parks. These are important. However, those that plan often don’t take into consideration the voice of the Earth. In the United States, most city land is either paved over or used to plant grass.

In rural areas, factory farms and monoculture crops like corn are incredibly destructive to the earth because of the way they are grown.3 Large-scale farming practices increase the human risk for diseases like Covid-19 because they erase the biodiversity of the region. Biodiversity is what keeps the planet and people healthy. Consumers of these products are city dwellers that are often unaware of the impact of their food choices.

In these conditions, we easily lose our sense of belonging to our local and global habitat. Zen Master Dogen’s Tenzo Kyokun provides one possible template from which to work from to restore a sense of belonging.

“When you take care of things, do not see with your common eyes, do not think with your common sentiments. Pick a single blade of grass and erect a sanctuary for the jewel king; enter a single atom and turn the great wheel of the teaching. So even when you are making a broth of coarse greens, do not arouse an attitude of distaste or dismissal. Even when you are making a high-quality cream soup, do not arouse an attitude of rapture or dancing for joy.” 4

In other words, use what we have to the best of our ability. Every grain of food matters and should not be wasted, because it is the body of the Buddha.

In order to achieve the goal of inclusive, safe, resilient, and sustainable communities, we must reduce food waste by grocery stores, restaurants, and families and ensure distribution so that waste does not go side by side with people going hungry. We must work creatively with and appreciate what we have been given.

We need imagination to use the land to its best ability, and to determine what to do with excess food. Urban planning could prioritize pourous sidewalks. The dirt right under our feet can be utilized for locally grown food, and as habitat for native plants, animals and insects. There is evidence of the desire to change.

In the city of Ames, Iowa, where I live there are incentives available to landowners to turn their grass into gardens that support diverse native grasses with deep roots that help absorb excess water from rain runoff. Around our home we have planted up to 60% of the land with prairie flowers and grasses. We’ve found that this action has attracted lots of important food pollinators like bees and butterflies and improved the overall health of our soil.

Also, instead of throwing our food waste into the garbage, 100% of our non-edibles are composted. The composted soil is then added into our garden’s kale, carrots, and peas to support their growth without the use of chemical fertilizers. We are careful not to throw away excess food, but to compost it. Others in our city also take their excess garden produce to food pantries and free meal programs for preparation and offering.

We have begun to seek to educate the local community through blog posts, letters to the editor and Dharma talks on the need for supporting biodiversity.5

We also support and have served on the Board of the Iowa Interfaith Power & Light, an organization whose mission it is to call attention to the role farmers can play in reducing CO2. 6

We are in the process of creating retreats where we practice cooking and eating in the way that Dogen recommends, and seeing the connection between our purchases at the grocery store, what is grown in the field, and what we cook in our kitchen.

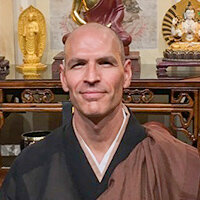

Rev. Daishin McCabe of Zen Fields is a dharma heir of Rev. Daien Bennage, with whom he studied in monastic residence for 15 years; he has also practiced in Japan at Zuioji, Shogoji, Kappa Dojo, Hokyoji, Hosshinji, and Gotanjoji. He has a B.A. in Religion and Biology from Bucknell University and training as a behavioral health chaplain. He's done significant work in practicing with trauma, both early childhood trauma and that which comes from systems and institutions.