Use of Cookies

Our website uses cookies to facilitate and improve your online experience.

Since 1991 Sotoshu has been engaged in a variety of activities under the banner of “human rights, peace and environment”. And since in 2015 all the members of the UN signed the agreement of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG’s) with the purpose of “Leaving no one behind”, Sotoshu has great interest in encouraging practitioners of this tradition, from the Bodhisattva's own vows, to commit in a practice that reflects these goals of including all beings in a better world.

Although all the 17 points of the SDGs are of vital importance to build fair, inclusive and respectful societies, the sixteenth point, “Peace, justice and solid institutions”, is one of the aspects that has touched the most our Zen Temple Magnanimous Mind, Daishinji. In our commitment to offer a practice that helps alleviate so much suffering in our country, we have launched campaigns to make our practice known as a transformational alternative to relate to life in a healthy way and modify how we relate to other beings and to life in general.

In Colombia we have experienced great suffering for decades, due to social injustice, economic imbalance, insecurity, lack of educational resources, war and drug trafficking, among others. But the violence is not limited to the political struggle, the interests of criminal organizations or the armed conflict. We can see it in the way we treat each other, racism, classism; in general, contempt for others and everything that is different. Having been born in a country that experiences so much suffering, when I first met Soto Zen in the mid-80s, I understood very early that this practice, as passed down from Shakyamuni Buddha, offers powerful elements to help us liberate other beings from suffering and to find relief to our own dissatisfaction. To arouse the aspiration for enlightenment involves decentering attention from our own need for gratification and taking care of others, just like a mother who takes care of all her children equally.

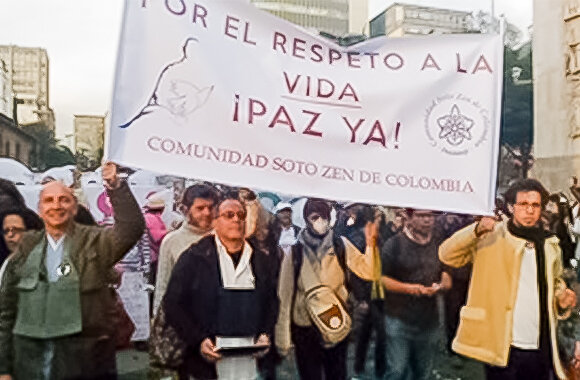

During the celebration of 110th anniversary of the arrival of Sotoshu in South America, held in Lima, Peru, in 2013, the group of teachers signed the commitment to hold a Latin American Zen Encounter that would include practitioners of various traditions, to promote the teachings of Zen Buddhism, to have a positive impact in our countries. Thus, in 2016, we held the Third Latin American Zen Encounter in Bogotá. At that time, the Colombian government was signing a peace agreement after more than 50 years of armed struggle with the FARC guerrillas. We proposed the Encounter as a concrete and positive response to alleviate the suffering of so many years of struggle and we offered our practice as a tool for the consolidation of a lasting peace and the construction of a healthy society.

At a global level, we are experiencing a historical moment of chaos after the recent pandemic, the economy hardship and numerous wars: there is a lot of uncertainty and a lot of fear. We think things have never been this bad. But if we look at the history of mankind, since immemorial time, the poisons of the mind have led nations to invade others out of greed or hatred. Already in Buddha's time there were numerous wars. In fact, ancient texts say that Shakyamuni Buddha himself not only preached non-violence and peace, but also went to the battlefield to prevent a war between the kingdom of Maggadha and the Vajji tribe, who disputed the hegemony of the waters of the Rohini River. Shakyamuni's words prevented King Ajjatasstru from attacking the Vajji. But in addition to border issues, Buddha influenced the internal condition of the kingdoms, addressing the sovereigns and proposing more benevolent policies that ended the abuses towards the people. The Master was no stranger to the suffering caused by some inhuman sovereigns, who took advantage of the misery of the people to enrich themselves, excessively increasing taxes and imposing severe punishments. Shakyamuni, in person, concerned himself with improving relations between the King and his people, wrote “The Ten Duties of the King”*1 in order to prevent the people from becoming corrupt, degenerate and unhappy due to bad government.

These are early evidences of how Buddhism has been concerned with bringing peace in a concrete way, beyond the walls of the temples themselves. However, we must understand that peace is not something external like weather conditions. Producing lasting peace is only possible through a joint and sustained effort, committing ourselves individually to transform our own way of relating to life. This is the Buddhist principle of non-violence, ahimsa, which not only means that no one should be harmed, but also it is our obligation to strive to promote peace by avoiding any warlike confrontation and everything that implies violence or the destruction of lives, including respect for animals and for nature. It is not possible to achieve peace abroad if society is not made up by individuals who are at peace with their own existence; individuals who, from their understanding, include others, and are tolerant of diversity and respectful towards others' ideas.

Dogen Zenji says that our practice of zazen is itself the dharma gate of ease and joy. But our practice is not limited to the sitting position. We must strive to express our understanding of this awakening in everyday life. To the extent that we act manifesting our certainty of the laws of existence to which we have awakened in our practice, we can act in opposition to egocentric tendencies and creatively influence the development of a healthy and peaceful society. Master Dogen gives us concrete tools to actualize our vows in everyday life. In the Tenzo Kyokun “Instructions for the Cook”, he talks about the importance of producing the three minds: magnanimous mind, joyful mind, and nurturing mind. It is about the attitudes that as Bodhisattvas we must seek to include others in a joyful way with a heart of a grandmother. Additionally, in the Shobogenzo chapter Bodaisatta Shishobo, he tells us about the Bodhisattva’s Four Embracing Dharmas, or attitudes to alleviate suffering. He invites us to be generous, careful with speech, to perform kind actions and to recognize the value of others. When our actions are directed by thinking that we can affect others in a positive way instead of causing them suffering, we displace self-focused attention and direct it to “everything else”. Thus, we can recognize the interconnectedness with everything and awaken to the incessant flow of reality. To build fair, balanced and peaceful societies, we must find peace by recognizing others and assuming responsibility for the consequences of own actions.

Thus, our vote as the Soto Zen Community of Colombia is to offer this practice in our country so that more people can find the dharma gate of ease and joy and creatively contribute to the construction of a respectful, tolerant, generous, inclusive and nonviolent society. Thus, we express our commitment to promote the construction of nations with solid, fair and peaceful institutions.

*1 Rahula, Walpola. “What the Buddha Taught”. Grove Press. N.Y. 1974. Pp. 85

Rev. Densho Quintero is a Soto Zen priest, Dharma heir of Shohaku Okumura Roshi. In 2013 he was appointed Sotoshu missionary teacher. At present, Densho is the head Teacher of (Magnanimous Mind) Daishin Temple of the Colombian Soto Zen Community in Bogota.

Comunidad Soto Zen de Colombia Daishinji (妙法山大心寺)

Address: Carrera 22 # 82-19 – Barrio El Polo Bogotá, Colombia